Why I’m a Pessimistic Optimist

(or if you prefer: An Optimistic Pessimist ☺)

I’m an optimist, because I’m positive we can correct the many and varied problems that affect us all. For example:

1. Like to get rid of unemployment? Simple: abolish minimum wage laws

The example of Hong Kong clearly proves this [page 25].

Minimum wage laws never affect the rich: they only affect the poor who have few, if any, qualifications or skills. If you were in that situation, you would have just two options: go on unemployment benefits—or turn to the far more lucrative field of crime.

2. With no minimum wage laws, expenditure on unemployment benefits will collapse: such welfare is only necessary when there is widespread unemployment.

3. Or inflation? The underlying cause of inflation is the printing of money, “financed” by governments which regularly spend more money than they receive in taxes.

How do they “make up” the difference?

➢ The central bank prints it.

➢ Stop printing money ⇒ no more inflation.

But you and I both know that the chances of any of those (and other government extravagances) actually being cut back, while not zero, is pretty damn close.

Which is why I’m (also) a pessimist.

And the underlying reason is:

The Curse of “Other People’s Money”

There’s nothing like “free” money.

We’d ALL like to have some, right?

But there are only two classes of people who can control and manipulate access to “Other People’s Money”:

1. Politicians, and

2. Bureaucrats

Politicians and bureaucrats work hand in hand. Their source of income is taxation—or “Other People’s Money”—so they live in a different world than the poor (or, for that matter, rich) taxpayer.

Don’t believe me?

Consider these three countries:

1. Brazil

2. Australia, and

3. United States

—and what they have in common:

Their capital cities—Brasilia, Canberra, and Washington—are government towns isolated from the rest of the country. In the cases of Brasilia and Canberra, they are geographically distant from the major industrial cities (as was Washington when it was founded).

What they also have in common is that their median salaries are way higher than their country’s median.

Brasilia

91% of jobs in Brasilia are in public sector “services.” Which means only 9% of Brasilia’s population is not living (directly!) on “Other People’s Money.”

Government jobs are so lucrative compared to the private sector that there are hundreds of applications for every vacancy in Brazil’s federal government.

Hardly surprising when you realize that Brazil’s average salary is R$8,560 ⁽²⁹⁾ per month—or R$102,720 per year. While if you land a job in Brasilia the average is R$138,200 per year—35.5% more!

Furthermore, upon retirement the ex-public “servant” receives a pension for 15 years which is the same amount as their salary in their last year of employment.

Canberra

If you’re working for Australia’s government bureaucracy in its capital, the median salary you can expect is A$80,587 per year.

This compares to the country average of just A$54,890.

An additional perk is that government employees receive an additional 15% of their salary paid into their superannuation fund, compared to a mere 11% for the average Australian worker.

As if that was not enough, the public service unions are now lobbying for a four-day instead of five-day week . . . with no cut in salary.

Washington

Similarly, in the US capital, government employees’ average salary is US$66,083 per year. Compared to an average of just US$45,760 for the country as a whole.

Taxpayers versus Tax Receivers

In every country there are two classes of people: the taxpayers and the tax receivers.

Taxpayers, in order to make money, must provide something of value which other people will pay for.

A problem that tax receivers don’t face.

Politicians and bureaucrats fall into the second category; as do recipients of welfare and other government “benefits.”

Unlike the average welfare recipient, politicians and bureaucrats are the agents who set the tax rules. So when the bureaucrats recommend to the politicians that taxes should go up (or vice versa), they’re not likely to receive much resistance.

A second source of “other people’s money” is the budget deficit.

When you or I spend more than we receive, we’re on the road to bankruptcy.

Whenever governments spend more than they receive, they print the difference. [The exceptions being those smaller countries which use another country’s currency.]

What IS Inflation?

Let's take a little trip to fantasyland.

In this rather small imaginary country there are just 3 players: you, me, and the government.

You and I each have a billion dollars [we might as well enjoy this little trip!].

The government also has a billion dollars: money you and I have paid in tax.

So the total money supply of this little country is $3 billion.

But the government also has the printing press. So it decides to print another billion dollars, thus increasing the money supply to $4 billion.

Our share of the total money supply has dropped from one-third each to one quarter.

But one thing has definitely not changed: the total supply of goods and services.

We know this as you and I are the only productive people in this economy. And the government’s printing press has not added one iota to the production of anything that anyone would wish to buy.

But something else has changed: the government now has 50% of the total spending power in this economy while each of us has only one quarter.

The reduction in our spending power from currency inflation—which is the technical term for the printing of money—is actually a hidden tax.

Few people complain when the government prints extra money; while any hike in income tax or other tax rates will fuel opposition.

Now, what do you think will happen when the government begins to spend that newly printed money?

With more money chasing the same amount of goods there’s only one possibility: prices will go up.

When most of us talk about inflation we mean rising prices. But prices cannot rise without cause.

One cause can be a shortage of certain goods, perhaps because a fire or other disaster in a widget factory has resulted in a temporary shortage of widgets.

But that will not result in prices rising for everything.

Only currency inflation can cause that.

The Inflation “Tax”

In the real world, the reduction in our spending power, thanks to the printing of money, is far from obvious.

For example, in the 2024 fiscal year (which, for some unknown reason, is 1 October to 30 September) the US government spent $1.83 trillion more than received.

A deficit equivalent to 0.854% of the total M3 money supply of $21.433 trillion.

Reducing everybody else’s spending power by almost 1%.

That doesn’t sound like a lot, but effectively it’s a tax on top of all the other taxes you’ve already paid.

The Hyperinflation “Super Tax”

When governments print money without limit, the result is hyperinflation.

The most well-known example of hyperinflation was during the Weimar Republic in Germany in the 1920s. Through World War I, the amount of German paper marks increased by a factor of four. By the end of 1923, it had increased by billions of times. From the outbreak of the war until November 1923, the German Reichsbank issued 92.8 quintillion paper marks. In that period, the value of the mark fell from about four to the dollar to one trillion to the dollar. [Emphasis added]

So that Germans had to cart around wheelbarrows full of paper money to go shopping!

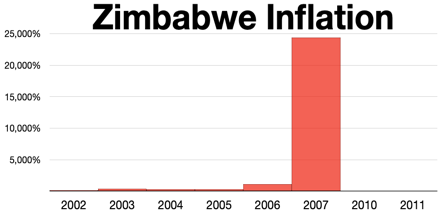

And in Zimbabwe the price inflation rate reached 25,000% in 2009.

During a hyperinflation, the spending power of the money in your wallet can shrink to almost nothing from one day to the next.

The combination of the power to tax and the power to print money reduces the incentive for the tax receiver to economize.

As is the case with anyone who receives “Other People’s Money.”

The Third Source of “Other People’s Money”:

Lobbyists.

As Professor Luigi Zingales, at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, puts it:

“When government is small and relatively weak, the most effective way to make money is to start a successful private-sector business. But the larger the size and scope of government spending, the easier it is to make money by diverting public resources.” ⁽³⁰⁾

Which exactly what lobbyists are paid to achieve.

In 2023, 12,937 registered lobbyists spent $4.26 billion in Washington DC on behalf of companies and associations like the US Chamber of Commerce.⁽³²⁾

$4.26 billion⁽³¹⁾ is a helluva of a lot of money in anyone’s vocabulary. And one thing you can be certain of: for-profit enterprises rarely spend money needlessly.

Thus, those 12,937 lobbyists (at last count) are aiming to achieve one of two objectives:

➢ Have a law or regulation passed that benefits their employer’s business; or,

➢ Prevent a law or regulation being passed that would negatively affect their employer’s business.

Politicians and bureaucrats can benefit from lobbying in several different ways. Here are a few:

➢ Donations to a politician’s campaign fund;

➢ Invitations to speak at an event: one of the “meet the Senator/Congressman” occasions; and,

➢ The promise of directorships or other perks upon retirement.

All laws and regulations benefit somebody at the expense of someone else.

For example, in Sydney, Australia, zoning laws, building, and related regulations add an average of $200,000 to the price of a house. That’s 12.5% of the median $1.6 million price of a Sydney home.

Which adds $200,000 to the resale value of a house that was purchased before those zoning and other laws came into effect.

And regulations can restrict competition, thus adding to the price the regulatees can charge.

As in New Hampshire, USA, where if you cut your own hair or somebody else’s without a licence you could go to jail for one year. Or if you’re lucky, just pay a $2,000 fine.

Others are just plain absurd:

➢ In Brisbane, Australia, failing to wave a “thank you” when another driver allows you to merge into his/her lane is a fineable offence

➢ In Florida it’s illegal to pass wind in a public place after 6pm on Thursdays

➢ In London, it’s illegal to wear a suit of armour in the Houses of Parliament (according to a law passed in 1313!!)⁽³³⁾

Regulations aren’t going away. Quite the opposite.

Since the foundation of the American republic in 1789, the US Congress has passed over 30,000 statutes, an average of 180 new laws per year.

That seems like a lot. But it pales by comparison to the number of regulations: in just the 22 years from 1995 to 2016, federal agencies in the US issued 88,899 new regulations.

An incredible 7,400 new regulations per year!

And that’s not counting the laws and regulations passed by state governments and city councils.

All to the benefit of those people who staff regulatory agencies. Every regulatory body is effectively a law unto itself, a mini dictatorship which has little to no supervision or restraint.

So it’s quite logical for me (and you!) to be an optimist at heart. But in the real world there’s far more for both of us to be pessimistic about.

⁽³⁰⁾ Finance professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, A Capitalism for the People: Recapturing the Lost Genius of American Prosperity

⁽³¹⁾ https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/summary

⁽³²⁾ See the top spenders here: https://www.statista.com/statistics/257344/top-lobbying-spenders-in-the-us/