My Not-So-Modest Proposals to Improve the Political Process

Herewith: fourteen entirely reasonable reforms that many people will find acceptable—the main exceptions being (surprise!) politicians and bureaucrats. Who, as our “Lords and Masters” must legislate them

So don’t hold your breath . . .

1. Appoint your own representative. Shareholder style.

In theory, you are represented in parliament by the person elected in your electorate.

But what if you didn’t vote for him or her? Do you feel you’re truly represented?

Can you withdraw your representation? Of course not. You’re saddled with whoever it is until it’s election time again. (And probably afterwards too.)

I don’t know about you, but I’d much rather choose my own representative than be stuck with someone I neither like nor agree with just because I live in a specific geographic area.

How about switching parliamentary representation to the company “proxy model.”

When you own shares in a company, you can either represent yourself and vote those shares at a general meeting or appoint someone to vote on your behalf. Specifying whether it’s “yeah” or “nay” on each specific issue.

Given today’s technology, there’s no reason why that model cannot be applied to parliament. (Companies use it all the time. It works.)

Elections as we know them would disappear. Instead, would-be representatives would seek our proxy. A proxy that could come from a voter in any part of the country instead of a specific geographic area; a proxy we could withdraw, switch, or restrict at any time.

Assuming the number of members of the parliament remains unchanged, the members elected would be those with the most proxies. In the US House of Representatives, for example, the top 435.

But, as we can simply login and switch our proxies at any time, those 435 members won’t necessarily sit in the House until the next election.

Or even the next day!

Say we gave our proxy to Bloggs who was the 435th elected ’cause we figured he was a good guy. But it turns out he’s a charlatan. If enough people think the same way, Bloggs would be thrown on his arse and replaced by Smith—who was number 436. No need to wait until the next election, or organize a recall, if such an option is available to you.

Or, if Bloggs was generally okay but you disagree with him strongly on a particular issue—whether it be climate change, abortion, same-sex marriage, or whatever—you could give your proxy on that specific issue to Jones, or someone else who agrees with you.

That’d sure as hell keep those pollies on their toes—and make “representative democracy” truly representative!

2. Referendums: When “We the People” Speak—and are Heard!

Supposedly, in a democracy, we the people are the rulers.

The reality is somewhat (actually quite, quite) different. Every two to six years, depending on where you’re living, you get to cast a vote. Usually, we have only two choices, thanks to the way the political process works.

The aim of every political party is to secure a majority of the parliament or congress, which enables it to rule. Sometimes, a coalition of two or more parties is needed to create a parliamentary majority.

Either way, as voters our effective choice is severely limited.

Switzerland offers a somewhat different model: the referendum.

If just 50,000 Swiss citizens—a mere 0.57% of registered voters—object to a law, they can call for a referendum. If a majority votes against the law, it becomes null and void.

While 100,000 citizens can propose an issue for a referendum to amend the constitution.

In Switzerland, the people can easily overrule the politicians.

Under the Swiss model, the pollies don’t always get their own way.

In 1974 I met a Swiss banker in Sydney who commented that he had always thought there were just far too many referendums in Switzerland.

Until he came to Australia.

Two years earlier the Labor Party had won the federal election after 23 years in the wilderness of Opposition. Led to victory by the charismatic Gough Whitlam, the Labor government tried to squeeze 23 years’ worth of what it believed were much needed reforms into just a year or two.

The result was destabilising and unnerving for too many people.

Had the Swiss model prevailed, many of those reforms would have been rejected by the voters—and Gough might have been re-elected instead of being thrown out of office.

3. Anyone Who Volunteers Him- or Her- self for Public Office Should Be Automatically Barred

For life.

Politics attracts people who like to have power over others. Those others being us.

That doesn’t apply to everyone who enters the political arena. Some are idealists who want to change the world—though to do so they need to have . . . power.

As a generality the pragmatists whose main focus is re-election tend to rise to the top.

Politicians tell us they’re there to “serve the greater good.” If that’s really the case, they should be happy to ban any power-luster who is, after all, only out to serve him- or her- self—at everybody else’s expense.

If volunteering for any political office is banned, those who really want the job will have to find a way to get themselves “drafted” by others. Which raises an interesting question: would anyone who really doesn't want the office accept it if offered?

4. Only Nett Tax Payers Can Vote

Think about it.

Every single person involved in government, politician or bureaucrat—with the few minor exceptions of the very wealthy—is a nett tax receiver.

Every single one of them lives on Other People’s Money, extracted at the point of a gun (doubt me? try not paying your taxes and see what happens).

Thus, they all have a vested interest in increasing the amount of Other People’s Money they can spend. Whether on themselves or on increasing the powers of their domain.

Hardly a surprise, then, that governments everywhere spend more money than they receive, with the rare and very occasional balanced budget.

If only the providers of Other People’s Money—nett tax payers—could vote, we could be pretty sure government budgets would balance pretty damn fast!

Unfortunately, by the same logic, the chances of nett tax receivers voluntarily cutting off their supply of Other People’s money is—how shall I put it?—considerably less than zero.

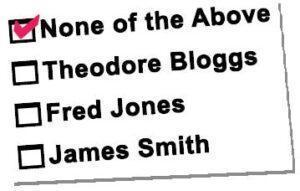

5. Add Another Option: “None of the Above”

Current voting systems all around the world offer you a limited choice: limited to the number of candidates on the ballot paper.

What if you would not vote for any of them? Well, you can always stay at home.

How about adding another option to the ballot paper: “None of the Above”?

Which would make little difference to the results unless 50% of the vote plus one, including “None of the Above” votes, was required to win.

Unless—as one comedian put it—”None of the Above” was at the top instead of the bottom of the ballot paper.

A joke—but just the sort of thing some politicians would certainly prefer!

5. Election by Phone Book?

National Review founder William Buckley once said he’d rather be ruled by the first 100 names in the New York telephone directory.

Not a bad idea . . . to start with.

Look at a phone book (if you can find one nowadays) and you’ll see that it begins with listings like AAA1 Repairs and AAAA1 Repairs.

By the time of second or third “phone book election,” I’ll bet that hopeful pollies will have all legally changed their names to, f’rinstance, AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA Donald Trump!

6. Preferential Voting

This system of voting, currently used only in Australia, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea on a national scale, is a simpler form of the more popular “run-off” election: When no candidate has 50% plus one of the vote, a second election is held with just the top two candidates on the ballot.

When there are just two candidates, whoever gets the most votes wins.

But with three or more candidates, preferential voting starts to get interesting.

Preferential voting means numbering all the candidates in order of your preference. So if Bloggs, Jones and Smith are the candidates, and you want Jones to win but detest Smith, you might vote like this:

2 Bloggs

1 Jones

3 Smith

The winner has to get fifty percent of the votes, plus one.

When the votes are counted only the first preferences—the 1s—are tallied. Say the count looks like this:

Bloggs 29

Jones 27

Smith 44

TOTAL 100

In countries like the U.S. and Britain with a “first past the post” system, Smith would be the winner—even though a majority of 56% voted against him.

But with preferential voting, since Smith does not have fifty percent of the votes plus one, there’s a second round: the preferences of the lowest candidate are “distributed.” In this case, that’s your candidate, Jones.

All his votes are counted again. But this time the 2s, not the 1s, are tallied. Those 2s are added to Bloggs’ and Smith’s 1s to give the final total. Let’s say 5 Jones voters put Smith as their second choice, while the other 22 went for Bloggs. The final result is:

Bloggs 51

Smith 49

TOTAL 100

So even though Jones, your favorite candidate, didn’t make it, at least that charlatan Smith didn’t get in—because your vote was counted twice.

When there are more than three candidates—as always happens in the Australian Senate polls—the process is the same if a little more complicated. They simply keep distributing preferences until they reach “the last politician standing.”

One downside is called the “Donkey Vote”: voters who simply number the candidates 1, 2, 3, 4, . . . from top to bottom. That can add up to 4% to the candidate whose name is first on the list.

Preferential voting might have changed the result in the US 2016 presidential election.

Trump won the electoral votes, but his national vote of 46.09% trailed Clinton’s 48.1%. Of the other parties, Libertarians won 3.28%, while the Greens achieved 1.07%.

According to a CBS News exit poll, in a two-candidate race 25% of Libertarian voters would have voted for Clinton, 15% for Trump, and 55% would have stayed home. The similar numbers for the Greens were 25% Clinton, 14% Trump, and 61% said they wouldn’t bother voting at all.

Preferences would increase Clinton’s vote total over Trump from 48.1%/46.09% to 49.19%/46.73%.

Not a big increase in Clinton’s margin. But possibly enough to change the result in one or two states, so increasing her electoral vote total. Though unlikely by enough to close the gap of 74 between her 232 electoral votes to Trump’s 306.

In 2020, when Biden won 51% of the national vote, making him the clear winner: preferential voting wouldn’t have changed that. Unless the “vote-againsters”—those didn’t vote for but against Biden or Trump—registered their distaste for both major candidates in sufficient numbers by giving their first preference to one of the minor parties or independent candidates.

7. Let’s Have Some Results

Every piece of government legislation is “sold” on the basis that it’s aimed to achieve certain results.

Instead of puffery, legislators should be required to specify the expected results in excruciating detail with a target date by which they will be achieved. In a reasonable time frame—say 18 months to three years maximum.

If those results are not achieved in the specified time, the legislation is automatically null and void. And the entire department in question is abolished.

8. The Venetian Model

An intriguing provision in the Republic of Venice was that every public official had to take an oath of office. From the Doge (equivalent of president or prime minister) to lowliest officeholder.

One of several reasons the Venetian Republic lasted for almost a thousand years—until Napoleon invaded in 1797.

The oath was not just a formality. Far from it: more a contract than an oath. Any officeholder who broke his oath could be sued and fined for the equivalent of breach of promise or breach of contract.

Similar to the impeachment process in the United States?

Not really.

True, the president of the United States takes an oath. And can be impeached for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

But the impeachment process is cumbersome: initiated by the House of Representatives by a simple majority, which is the equivalent of an indictment, and then tried by the Senate, conviction requiring a two-thirds majority.

Only two US presidents have ever been impeached: Andrew Johnson (1868) and Bill Clinton (1998). Both were acquitted by the Senate.

In Venice, by contrast, there was a special attorney’s department whose primary function was to prosecute officeholders who had broken their oath.

And they often were. From the Doge to Admirals of the Fleet, the Venetian equivalents of Ministers and Congressmen—to the lowliest public official. Sometimes they were even bankrupted by the amount they were fined.

Adopting a similar procedure would certainly keep politicians and bureaucrats on their toes!

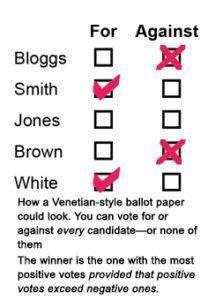

9. Negative votes

Another interesting feature of the Venetian Republic was negative votes.

Instead of just voting for someone, you could also vote against. The winner was the candidate with the most positive votes, provided that the total positive votes exceeded the total negative votes.

At the moment the only way you can vote against someone is to vote for someone else. Or stay home on election day.

Imagine what might happen if you could cast negative votes along with positive ones.

For example, just prior to the 2016 American presidential election polls gave Donald Trump an unfavorable rating of 55%, slightly better than Hillary Clinton’s negative rating of 55.3%.

Had voters been able to cast negative votes they might both have lost. Fancy that!

Similarly, a September 2020 Gallup poll reported Trump’s and Biden’s favorable/unfavorable ratings as 41/57 and 46/50 respectively. If negative votes were possible, another pair of losers.

This is hardly untypical. In a November 2018 Australian poll in asked the question:

“Who Would Make the Worst Prime Minister?”

36% of respondents nominated Australia’s opposition leader, Bill Shorten, as the better PM, while 50% said the opposite.

The sitting prime minister, Scott Morrison, didn’t do that much better: 42% for, 47% against. A race to the bottom!

And in Britain, an April 2018 poll measured then-PM Theresa May’s personal approval rating at -8, while the opposition leader at the time, Jeremy Corbyn, weighed in at -19.

Given the option of negative votes along with positive ones (don’t hold your breath) an overwhelming majority would probably have voted for none of the above!

The implications of negative voting are fascinating.

Currently, a political party’s aim is to field a candidate who will receive more votes than the opponent. No matter that all the candidates have approval levels under 50%.

As a joke going around during the 2016 US presidential election put it:

➢ What’s the good thing about Trump? He’s not Hillary.

➢ What’s the good thing about Hillary? She’s not Trump.

Not very funny!

At the moment, from the political parties’ point of view the key to victory is not to have a candidate who the majority of voters approve of (though that’s a big bonus!) but to have a candidate whose disapproval rating is lower than the opponent’s.

Negative votes turn things around 180 degrees. When the winner is the one whose positive votes must exceed his or her negative ones, a low disapproval rating would suddenly become essential to victory.

Although . . . what would happen when there’s no clear winner in the first round, so there’s a run-off—and negative votes exceed positive votes for both remaining candidates?

Start over??

10. By Lot(tery)

Another Venetian practice.

At one point in its history, a short list of candidates for certain offices was chosen by vote of the General Assembly or (later) by a committee.

Those candidates’ names were all put in a jar and the name drawn out was the new officeholder.

With the aid of modern technology, we could take this idea a few steps further.

The name of everyone eligible to vote could be put into a database, and the first 435 names thrown up, like a lottery, would make up the next US congress.

Another 100 (or more) would have to be drawn as, inevitably, more than a few of those first 435 people would probably refuse the honor.

The chances of any one of those “winners” being re-drawn in the next lottery is so close to zero it’s probably not worth thinking about.

11. Sunset Laws

Like food products and other perishables, every law and regulation should come with an expiry date. Let’s say: a month or so before the next election.

That way, the politicians would be so busy reenacting all the old laws they wouldn’t have enough time to think up too many new ones.

12. A Guaranteed Way to Cut Government Spending

Governments everywhere have the great advantage of never having to worry about bankruptcy.

When you spend more than you earn, you’re broke. When a business’s sales fall too much (or expenses are out of control) the liquidators are called in.

When a government spends more than it “earns,” it merely prints the difference.

The true Master of Governments—the bureaucrats rather than the politicians—jealously guard their privileges. And one of those privileges is their annual budget.

As there is always some politician attempting to score brownie points by finding a way—any way—to trim government spending, department heads ensure that when it’s time to prepare next year’s budget, they all make sure that they are in a position to argue that they simply don’t have enough money.

To “prove” it, at the end of every financial year every government department rushes to spend the last of its money so next year’s budget won’t be cut.

Change the incentives.

For every dollar they come in under budget, pay fifty cents as a bonus to the staff. Hell, pay out the lot.

Preferably as retirement bonuses for those junior bureaucrats who’d rather go fishing.

But then . . . the department’s pre-distribution spending becomes next year’s budget.

Waste will disappear almost overnight.

Well . . . at least until the bureaucrats figure out a way around it.

13. “Election” by Assassination

Science fiction offers a number of “off-the-wall” examples. The most outrageous being in Robert Sheckley’s short story, A Ticket to Tranai, first published in the October 1955 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine.

SPOILER ALERT! If you’re an SF fan who has never read this story I suggest you skip immediately to item #7.

Or: you can read A Ticket to Tranai online here (and then come back . . . and if you’ve never read a Sheckley story before you’re in for a treat.)

Marvin Goodman travels from Terra to Tranai where, shortly after arrival, he meets the immigration minister who asks him if he would like to become Supreme President.

After considerable persuasion, Goodman agrees thinking, “Well, someone had to rule. Someone had to protect the people. Someone had to make a few reforms in this Utopian madhouse.”

A moment later, the President rushes in and, as he is about to pass his medallion of office to Goodman, suddenly explodes, leaving Goodman staring at a headless corpse.

It turns out that any citizen may register his or her dissatisfaction with any sitting official, whether President or dogcatcher, by visiting a Citizens Booth to register that protest.

When those protests reach a certain number (which Sheckley does not specify) the medallion which every official wears blows up.

Under such an “election” process nobody in his or her right mind would accept the “honor” of being “president.” If that’s a flaw (and I’m far from convinced it is) so be it.

“None of the above” in spades!

Any volunteer for the post who thinks the presidency is a ticket to power is unlikely to have very long life expectancy.

“Don’t you still want the Presidency?” asked Meith [the immigration minister, at the conclusion of Sheckley’s story].

“No!” [Goodman replied.]

“That’s so like you Terrans.” Meith remarked sadly. “You want responsibility only if it doesn’t incur risk. That’s the wrong attitude for running a government.”

Replace “Terrans” with “politicians” in the previous sentence and it makes almost universal sense.

Sheckley’s system could be made less lethal (but no less effective) with the aid of modern Technology, into—

14. “Instant Recall”

Voters could simply register their disapproval of any official, either over the internet or in person. And when those “negative votes” reach X% (I would suggest 33%; but no doubt politicians, were they to accept such a reform, would insist on at least 50% plus one).

When (or if) the “magic number” is reached, that official is out on his or her you-know-what.

Existing recall provisions, mainly in the United States, are effectively a second election. This one focused on unseating the existing “representative.”

The “Instant Recall” process applies to all government office holders. And the “votes” are cumulative. Thus (hopefully) forcing politicians to be on their best behavior all the time rather than just at election time.

And finally . . .

15. An Almost Painless (Australian) Proposal for Taxpayer “Relief” By Enabling Voters to Show Their Respect for Politicians in a Suitably Appropriate Manner

By positioning dunnies (Australian slang for outhouses) atop the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Parliament of Australia, as sketched in above, Australians would be able to show their true appreciation of politicians.

At a charge of say $10 a time (double when Parliament is in session?) it’s conceivable that the government could pay off the national debt in a painless yet highly pleasurable way.

As an extra incentive, the ten bucks could be tax-deductible!

And there’s no reason (other than fastidiousness) why other parliaments all over the world could not adopt the same proposal.

*In case you’ve never come across the term “dunny” before, read on:

The Aussie Dunny Poem

They were funny looking buildings, that were once a way of life,

If you couldn’t sprint the distance, then you really were in strife

They were nailed, they were wired, but were mostly falling down,

There was one in every yard, in every house, in every town.

They were given many names, some were even funny,

But to most of us, we knew them as the outhouse or the dunny.

I’ve seen some of them all gussied up, with painted doors and all,

But it really made no difference, they were just a port of call.

Now my old man would take a bet, he’d lay an even pound,

That you wouldn’t make the dunny with them turkeys hangin’ round.

They had so many uses, these buildings out the back,

You could even hide from mother, so you wouldn’t get the strap.

That’s why we had good cricketers, never mind the bumps,

We used the pathway for the wicket and the dunny door for stumps.

Now my old man would sit for hours, the smell would rot your socks,

He read the daily back to front in that good old thunderbox.

And if by chance that nature called sometime through the night,

You always sent the dog in first, for there was no flamin’ light.

And the dunny seemed to be the place where crawlies liked to hide,

But never ever showed themselves until you sat inside.

There was no such thing as Sorbent, no tissues there at all,

Just squares of well read newspaper, a hangin’ on the wall.

If you had some friendly neighbours, as neighbours sometimes are,

You could sit and chat to them, if you left the door ajar.

When suddenly you got the urge, and down the track you fled,

Then of course the magpies were there to peck you on your head.

Then the time there was a wet, the rain it never stopped,

If you had an urgent call, you ran between the drops.

The dunny man came once a week, to these buildings out the back,

And he would leave an extra can, if you left for him a zac.*

For those of you who’ve no idea what I mean by a zac,

Then you’re too young to have ever had, a dunny out the back.

(*A “zac” was slang for a sixpence coin before decimal currency came into Australia in 1966)

And . . . One Other Thing . . .

As you may have gathered, I am somewhat cynical about politics and politicians.

In my novel Trust Your Enemies the character Karla Preston summarized my views when she commented that “Politicians are just used car salesmen in fancy dress.”

Perhaps you think this is a slur on used car salesmen.

Not so.

Used car salesmen may have a poor reputation—which was certainly the case when I was younger. But there are enormous, and very important differences, between voting for or against a politician and buying a used car.

First of all, you have an enormous selection of used cars to choose from. Not just two, or if you’re lucky three, different models.

Second, you’re not stuck with one used car salesman for the next two to six years.

Third, make sure your used car comes with a guarantee. Then, if you purchased what turns out to be a clunker, you have the option of redress.

By comparison, a politician’s election “promises” do not come with any guarantee.

If reneged upon, you have to wait for another two to six years before you have the opportunity to throw the scoundrel out.

With zero guarantee of success.

Nevertheless, I suppose that those of us who live in democracies should be thankful that we can, at least, vote against the greater of two evils. An option people in one-party states are denied.

Unfortunately, the lesser of two evils is still evil.

PS: By the way, if you think any of these suggestions are likely to be implemented in my lifetime or yours (pick whichever is longer) please send me a package of whatever you’ve been smoking. Must be really hot stuff.

Quite clearly, our Lords and Masters will be in no hurry to adopt any of these modest and highly reasonable proposals: that would entail reducing their powers over us, a proposition they will only be willing to accept under extreme duress.