Give Your Kids and Grandkids [even yourself!] a “Money Tree”

True, money doesn’t grow on trees

But it sure grows like topsy somewhere else

It’s never too early to teach your kids about money. Indeed, best to start when they have no idea what money is.

Which is what I’m doing right now: setting up “money trees” for my two grandsons, three and five-years-old, respectively.

By the time they turn 18, they should have an excellent idea how to let money grow. And may even be able to pay their own university fees!

To achieve this goal, I’ve opened an account for each of them, with an initial deposit of $1,000.

With current levels of interest rates, you might be wondering what’s the big idea?

That $1,000 won’t be sitting in a bank. It will be fully invested in the stock market. Simply for the reason that over time the return on stocks averages between 7% and 11% per year.

For example, $1,000 invested in the American S&P 500 index 38 years ago, on January 1, 1986, would have risen to $20,913.92 by the end of 2023. For an annual increase of 8.33%.

Try getting that at your local bank.

But that does not include dividends.

Assuming an average annual dividend of 3% (after tax), over that 37-year period dividends would have added a not too shabby $1,595.87.

A tidy bonus, don’t you think?

But if those dividends had been reinvested in the index every year, the end result would be a whopping $38,875.

For an eye-popping return of 10.4%.

Per year!

And when investments are made in stocks or funds with Dividends Reinvestment Plans (otherwise known as “DRIPs”) the transactions’ costs—other than new stock purchases—will also be zero.

The key to setting up a “money tree” is to:

LET Your Money Grow

We normally talk about making money.

But when you plant a tree you can’t “make” it grow.

The tree will grow all by itself.

You can only help it grow faster and bigger. By planting it where there's plenty of sunshine, watering it, adding fertilizer, and pruning it from time to time.

The secret to letting your money grow like trees do (all by themselves) is to harness—

The Magic of Compound Interest

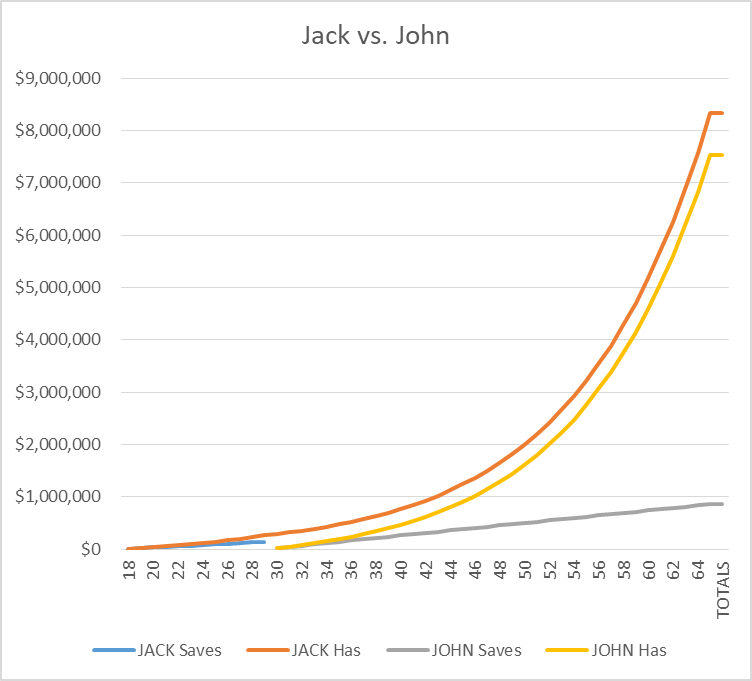

To appreciate this “magic,” consider the story of Jack and John.

They were both 18 years old when they finished high school.

Jack got a job right away, fixing up cars, which was all he wanted to do anyway.

He put $1,000 per month into a stock market mutual fund with an average return of 10% per year, and continued to do so for the next 12 years, until he needed all his earnings to send his kids to school.

John went on to university, took a year’s break after he graduated to see the world, and then went on to get an MBA.

He got a higher-paying job than John’s, bought a BMW, got married, and didn’t get around to thinking about his retirement until he was 30.

Then he contributed $2,000 per month to the same fund as Jack, and continued to do so until he retired at age 65.

All told, John invested $864,000 while Jack contributed just $144,000. At age 65, which of the two has more money, assuming the mutual fund paid a steady 10% per year?

Intuitively, it would seem that John must have more money. Which is what most people conclude. But that is to ignore the magic of compound interest.

When John started investing, Jack already had $269,442 in the fund. Jack never added another penny; but thanks to the magic of compound interest when they both retired at the age of 65, John had $7,537,995; but Jack had nearly a million dollars more: $8,329,174. Because compound interest is so powerful, John never caught up.

The term “compound interest” simply means interest on interest. As you can see from the picture, by the time John started saving more than half of Jack’s $269,442 was interest or interest on interest.

If you’re wondering where you can get that 10% return, you’re missing the point.

Which is:

Regardless of the rate of return (whether 1% or 100%)

Jack ALWAYS beats John

Enter: the “Investment Guru of the Month”⁽²⁾

At this point in the conversation, the Investment Guru of the Month usually chip in with some comment like:

“Boy, that’s a long time!

“Wouldn’t you rather get rich tomorrow, or next week?”

We’ve all heard stories about someone who made a killing in the market, businessmen who floated their company on the stock exchange and became zillionaires overnight, or the friend of a friend who turned a few thousand dollars into hundreds of thousands trading commodities.

But stories like these—when they’re true—are just the tip of the iceberg. What you hear is the sudden appearance of someone to wealth and prominence. What you don’t hear about are the years spent accumulating capital, and the knowledge and experience that established the foundation for supposed overnight success.

Such realities never faze those “Midases” among us who are always trying to seduce us with a broker’s latest “hot tip”; the mailshot touting some investment guru’s incredible ability to pick stocks that will double or triple your money almost instantaneously; or the mutual fund flaunting the 68% return it made last year (conveniently “overlooking” the fact that it lost money in the previous three).

We would all love to win the lottery and Investment Gurus always have a new get-rich-quick scheme up their sleeves ready to spring on us in our next moment of weakness.

All the Investment Gurus' glowing attempts to separate us from our money won’t change the fact that there is only one road to wealth:

Compound interest.

Plus time.

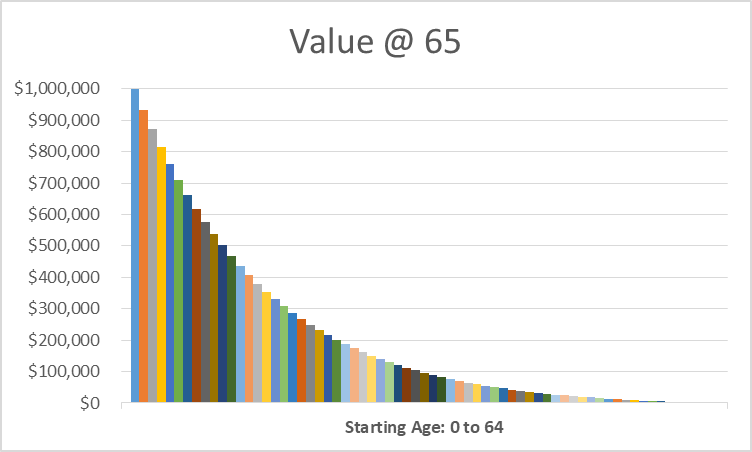

And the earlier you start, the greater the multiplying power of the “magic of compound interest.”

As the following chart demonstrates.

If you start a kid’s “Money Tree” at birth, he or she could be able to retire at 65 as a millionaire—assuming a steady return of 7% per year.

For a mere $57.80 per month!

$57.80 per month into a million. A pretty conclusive demonstration—I would argue—for the “Magic of Compound Interest.” Even though the tax effects are missing.

But neither this example, nor the story of Jack and John, are examples from the real world.

After all (sad to say) there’s nowhere you can get a constant interest rate of 7%, 10%—or any other rate of interest over an extended period of time.

Unless you “invest” with someone like Bernie Madoff. Who promised—and paid—high returns to his investors. Except that those payments didn’t come from a successful investment strategy, but from the money new investors put into his fund.

In other words, it was a Ponzi scheme. The largest in history, worth about $64.8 billion. An “achievement” for which he was sentenced to spending the rest of his life in jail (where he died pretty quickly).

That’s the bad news.

The good news is: you can actually do better.

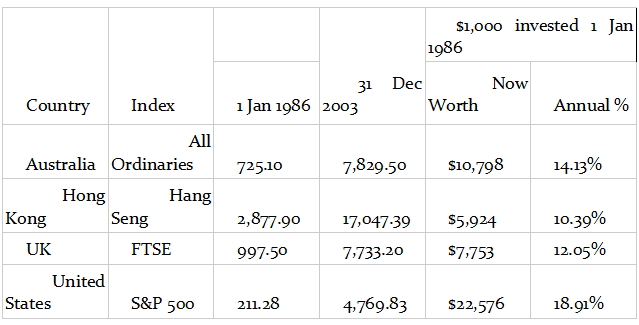

Here are examples, from four different stock markets, of how a single investment of $1,000, made in January 1986, would have grown in the 38 years to December 2023:

As you can see, the average annual increase in value over time ranges from 10.39% to 18.91%.

But that merely counts the change in the capital value of the stocks in the index. When we add in the dividends that would have been received, and assume they had been reinvested every month, the result is significantly different.

As you can see here:

The calculation is based on the assumption of an average dividend yield of 5% (or 3% after tax, except for Hong Kong where dividends are not taxable).

Setting It Up: the Nuts & Bolts

When it comes to investing in stocks, there are two fundamental strategies.

1. To beat the market—in other words, to do better than the second strategy, which is,

To simply own the “market as a whole” by investing in an index fund or ETF which aims to buy all the stocks in the index in the same proportions as they are counted in the index itself.

Strategy #1

There are two “simple” ways to beat the market:

1. Find the next Warren Buffett.

For example, every $1,000 invested in the stock of Buffett’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, on 1 January 1986 rose to $183,943.67 by 31 December 2022. For an annual return of 15.1%.

But if you (or your grandparents) had been prescient enough to have invested $1,000 back in 1965 when Buffett took over Berkshire Hathaway, it would now be worth $36,416,130.

An average annual increase of 19.9% . . . for 57 years!

2. Alternatively, you could do it yourself.

You don’t need to be another Warren Buffett to “beat the market.” But you do need to invest a considerable time and energy into analyzing and choosing which stocks to buy. And then monitoring them all.

Strategy #2

Much simpler: buy the “market as a whole.”

By investing in a fund or ETF that tracks the market index.

Which fund or ETF to buy?

Assuming that all index funds are essentially similar in that they own the stocks in the index in the same proportions as the index, there is just one final consideration:

Transactions Costs

To maximize your returns over the long-term, regardless of the investment strategy you follow, it’s essential to keep transactions as low as humanly possible.

As a general rule, there are just two kinds of transactions costs:

1. Brokerage fees; and,

2. Management fees when you invest in a fund or ETF.

3. Plus: when you “do it yourself,” the “opportunity cost”⁽³⁾ of your time.

To appreciate why this is such an important issue, let’s examine the impact of transactions costs on long-term investments.

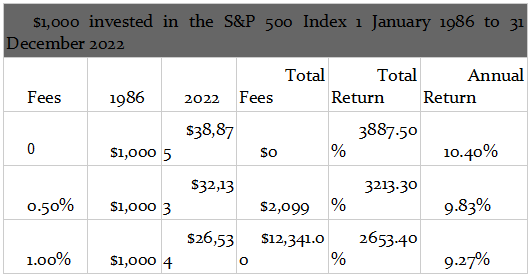

I’m sure you’ll recall our earlier example of how $1,000 invested in the S&P 500 index 37 years ago, on January 1, 1986 would, with dividends reinvested, compound to $38,875 by the end of 2022. Producing an annual increase of 10.4% per year.

But we hadn’t “added” in transactions costs.

Had that same amount been invested at the same time in a fund or ETF following the S&P 500 index, with total annual fees of a mere 0.05% [just ½ of 1%!], the value of that investment as of December 31, 2022 would be $32,133.

A difference of $6,742.

20.98% less!

The actual fees incurred over that 37-year period were just $2,098.71—31% of the total difference.

What caused that difference?

Compound interest: which works both ways.

As we are both aware, the higher the rate of interest the greater will be the rise in value over time.

At the same time, transactions costs reduce the amount of money to be compounded—so also reducing the final balance—regardless of the rate of interest.

We’ve identified the power of compound interest when it’s working for us. But for long-term success it’s essential to realize what can be the incredible negative impact from just a small but recurring expense.

To appreciate the impact, consider the result if the fund’s fees were twice as high: 1% per annum.

The hike from ½% to 1% doesn’t seem like a lot.

But the difference after 37 years of compounding is more than a double: that $1,000 compounds into just $26,534.

A drop of $12,342—46.51% less!

Which is why it’s essential to cut transactions costs to as close to zero as possible.

So keep that in mind whenever you invest in a fund or ETF. (Or making any transaction for that matter.)

When looking at different index funds, the fundamental metric is the fund’s transactions costs:

⇒ the fund with the lower transactions costs should be the better investment.

In principle, two funds both investing in the same index, with identical transactions costs, should have equal performance.

But one other factor could be the fund’s size: to match the performance of the index, the fund should own stocks in exactly the same proportions as they appear in the index. As few stocks offer the option of fractional shares, smaller funds may not precisely emulate the index.

The alternative to “buying the market as a whole” is:

The “Do-It-Yourself” Approach

This strategy is far more complicated and time consuming.

“Buying the market as a whole” effectively requires one decision: find the ETF or index fund with the lowest transactions costs.

Needless to say, if you “do it yourself” you also need to keep your transactions costs as low as possible.

But this approach entails making many other decisions

Just for starters: What to buy (or sell), and at what price?

Once you own something, you must continually monitor its progress. The management can change—or be incompetent; a new competitor could steal your company’s customers—just to mention two of the many changes that could turn what you thought was a great investment into a turkey.

And inevitably, while learning how to find that “great investment” you’ll sometimes make mistakes.

Mistakes that, in the market, will cost you money.

Not just today, but into the future—thanks to the negative power of compound interest.

Let’s assume that to achieve success following the “Do It Yourself” Approach you will need to spend at least one hour per day studying the market.

An alternative is to work an extra hour a day. And put those extra dollars (whether or $20 or $200) into that fund or ETF.

So increasing the amount of your money that is compounding.

Chances are you’ll do better over the long-term than if you spent those extra hours studying the market in an attempt to beat it.

It’s Not Just the Money . . .

The money sounds great, but it’s not the only purpose of setting up a “money tree” for your kids and grandkids.

And nor is the only aim to persuade them that saving for the future is a fantastic idea.

Which—needless to say—it is.

The Primary Aim

While you may have taken care of their retirement, at least financially, got them to “pay themselves first” (saving money before spending any); and made them computer literate at an early age, we still haven’t reached the “main event.”

Which is to make them future-oriented.

Most people’s “time horizon” is a few weeks or months. Occasionally: years.

For example, many moons ago I was sitting in the Parliament House office of Australia’s new Treasurer, shortly after his party had succeeded in taking office from the opposition party.

I was trying to persuade him that the economic measures they took now would determine the economic environment when they had to go to the polls again in three years’ time; so determining whether or not they would win.

I might as well have been talking to myself. Anything that was likely to happen more than three weeks in the future simply could not and did not exist in this man’s mind.

And did you ever know a teenager (including yourself) who ever seriously considered what life might be like when he or she turns 65?

I’d be surprised if there was just one teenager like that per million.

A simple experiment: ask anyone of any age whether they would prefer an ice cream today, or two ice creams next week.

I’m willing to bet that most everyone will take the first choice.

The Ice Cream “Lesson”

A friend of mine used ice creams to teach his children the value of delayed gratification.

An ice cream truck came past his house every day of the week. His kids all loved the ice cream that cost 50 cents. So every day he gave them 30 cents.

They had the option of buying a 30-cent ice cream—or waiting one day so they could “save up” for their favorite.

[Needless to say, 30-cent ice creams are something from the distant past. But . . . all his children are now financially-secure parents.]

“Games” like that, and the pleasure of watching their (and your!) “money tree” grow, will help to make them more future-oriented.

Learning to regularly “pay yourself first” is both the basis of financial security—and success in life

Most of the world’s most successful people have a time horizon that can be measured in decades. For example,

Stories about Warren Buffett’s frugality (some call it miserliness) are legion. One day Warren Buffett was riding the elevator up to his office on the 14th floor and there was a penny on the floor. None of the executives from construction conglomerate Peter Kiewit Sons, in the same elevator, took any notice.

Buffett leaned over, reached down and picked up the penny.

To the Kiewit executives, stunned that he would bother with a penny, the fellow who would one day be the richest person in the world quipped, “The beginning of the next billion.”

Buffett is an extremist on the subject of money. And nowhere is his extremism more evident than when it comes to spending it.

Or, to be more accurate, not spending it.

The basis of his frugality is his future orientation. When he spends a dollar — or scoops a dime off the street — he’s not thinking of today’s value of that money. He is thinking about the value that money could become.

For Buffett, thrift isn’t just a personal virtue but an integral aspect of his investment method. He admires managers like Tom Murphy and Dan Burke (of Capital Cities/ABC) who “attack costs as vigorously when profits are at record levels as when they are under pressure.” He was a fan of Rose Blumkin, whose motto was “Sell cheap and tell the truth,” long before he bought her business, the Nebraska Furniture Mart. She cut costs so ruthlessly that she drove her competitors out of business. Major national furniture chains simply avoid Omaha because they know they cannot compete.

Buffett loves managers who ensure their companies live below their means. While Buffett and Charlie Munger were accumulating stock in Wells Fargo, they found out that Carl Reichardt, the bank’s chairman, had told an executive who wanted to buy a Christmas tree for the office to buy it with his own money, not the bank’s.

“When we heard that, we bought more stock,” Munger told shareholders at the 1991 Berkshire annual meeting.

Frugality is a natural aspect of both Buffett’s and Soros’s characters. As their wealth increased, both indulged in minor extravagances. Minor compared to their wealth. Buffett bought an executive jet he named The Indefensible. Aside from his apartment in Manhattan, Soros owns a beach house on Long Island, a country home in upstate New York and a house in London.

But wealth didn’t change their natural frugality. It’s easy to see how the consequence of living below your means is important when you’re starting out. It’s the only way you can accumulate capital to invest. What’s less obvious is how this mental habit remains crucial to your investment success even after your net worth has soared into the billions.⁽⁴⁾

Very simply, without this attitude to money no one will keep what they’ve earned. Spending money is simple—anyone can do it. Making and keeping money is not.

With any luck, by the time your children or grandchildren turn 18, they should appreciate the value of keeping what they have, and add to it by living below their means.

Compound interest plus time is the foundation of every great fortune.

So while your kids and grandkids may never join the Forbes 500 list of the world’s richest people, they should at least be able to retire in comfort.

⁽²⁾ Awarded [rarely!] to the investment advisor whose most recent prediction has just come true.

⁽³⁾ The income you could have earned if you’d worked those extra hours instead.

⁽⁴⁾ The Winning Investment Habits of Warren Buffett & George Soros, (Inverse Books: Hong Kong, 2004) pages 159-160.